[People News] The September sky sees summer’s charms fade with the greenery, and rivers quiet their rushing joy. Yet in human history, September ushers in a season of chilling repression.

September’s Grim Winds · Keyboard Politics in East and West · A Tower-Climbing Master

On September 10, American right-wing conservative activist, writer, and media figure Charlie Kirk was brutally gunned down by assailants during a university lecture. His death ignited a direct clash over left- and right-wing ideologies across the United States and even reshaped the political landscape of Europe.

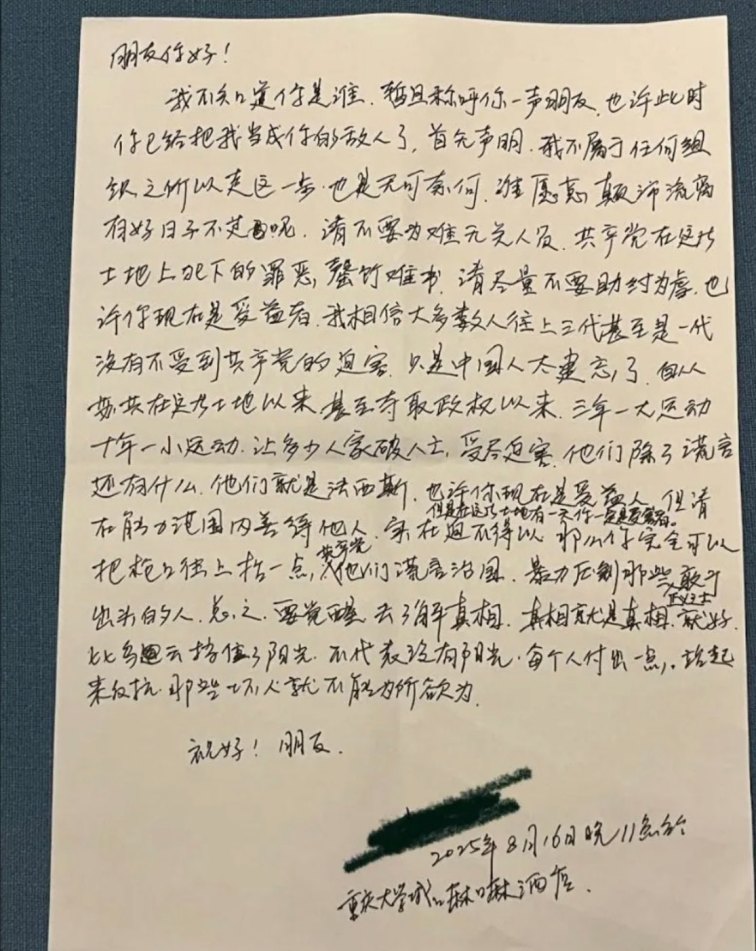

Coincidentally, less than a week later, on September 16, mainland Chinese blogger Hu Chenfeng—who had over a million followers—was suddenly banned across all platforms. This young influencer, predicted by some to become “China’s version of Charlie Kirk,” had recently gone viral with his satirical classification of “Apple People vs. Android People.” The phrase struck a nerve by starkly exposing China’s pervasive wealth inequality and insurmountable class divide. Inevitably, it triggered the regime’s political sensitivities, and Hu was swiftly handed a “silencing package.” His internet “social death” exploded like a powder keg, pushing the news of his ban to the top of trending lists. Online discussions of the “Hu Chenfeng phenomenon,” “Hu-ology,” and “Hu’s Tower Studies” quickly spread and went viral across the Chinese internet.

A comparison of these two internet heavyweights from East and West reveals striking similarities. Neither had elite university degrees nor privileged educational backgrounds, but both built their personal brands and standout personas through individual effort and skilful use of social platforms. Both espoused conservative-leaning, right-wing viewpoints, became famous for their eloquence and combative debating style, and excelled at sparring in public with opponents holding opposing views. Because of their firm defense of their stances and values, both faced criticism and threats from opponents. And in their roles as iconic figures of “keyboard politics,” both endured tremendous political pressure and unpredictable personal risks.

By comparison, Charlie Kirk is more mature and steady, with a larger fan base and greater influence. Many Chinese netizens believe that, given a looser political environment and broader boundaries for free speech, it would only be a matter of time before Hu is shaped into China’s version of Charlie Kirk.

Set against the CCP’s harsh speech controls and political atmosphere, many of Hu Chenfeng’s public commentaries have been hailed as classic works of “Tower Studies.” So-called “Tower Studies” refers to the methodology of “invisible rushing the tower”: online political warriors who, well-versed in the regime’s political ecology, speech boundaries, and legal red lines, operate under the guise of obeying the rules while actually using coded language or innuendo (“those who know, know”). In doing so, they manoeuvre freely in society’s forbidden political zones, deconstructing and mocking topics the authorities forbid touching. This not only satisfies the audience’s internal political cravings but also serves as a form of political awakening for the public. Put simply, it is the skill of walking a tightrope and skirting the edges of taboo topics inside the political danger zone, and doing so openly in front of the public—still managing to “harvest” the government in reverse, making it pay an “intelligence tax.”

How did Hu Chenfeng manage to reach this point? To understand that, one needs only look at his less-than-glamorous, yet equally remarkable, slices of life.

From Fixing Cars to Fixing Society · An “Android Life” Turned Apple Victory · A Purified Version of China’s Yu Jie

According to some online sources, Hu Chenfeng, born after 1995, comes from a third- or fourth-tier city, with parents of ordinary background. His highest level of education was high school. After around 2015, he worked as a car mechanic, on manufacturing assembly lines, tightening screws, and later in private equity. However, Hu described himself as a passionate reader and a diligent thinker. His early experience of the hardships of “Android people,” mingling with large numbers of working-class labourers, gave him a profound understanding of the gruelling struggles of ordinary lives and the extreme inequality in Chinese society.

The rise of short-video platforms and self-media gave him a legitimate outlet to express his “grassroots wisdom” and anger at injustice, and it also fueled his personal rise. Perhaps by fate, Hu’s outward image naturally conveyed a “people-friendly” persona: a forever youthful face with a touch of slyness, set on a thin, fragile frame, dressed in slightly oversized, student-style clothes from head to toe. This conveyed an unguarded, unpretentious authenticity. Yet when contrasted with his calm composure, powerful eloquence, and commanding presence in debate, this paradoxical mix of low-key appearance and high-capacity inner core made it nearly impossible for him not to become popular.

Around 2020, Hu Chenfeng began posting short videos on Douyin and Bilibili. His early content mainly consisted of everyday life records, simple in style and focused on small-city routines. Starting in 2021, he launched the “100 Yuan Purchasing Power Challenge” series, attempting to pivot toward social observation. Through street interviews, he showcased the hardships of ordinary people’s lives, quickly attracting attention. In 2023, he quit his offline job to operate his self-media full-time. His accounts grew explosively: 1.11 million followers on Douyin, 787,000 on Bilibili, and 226,000 on Weibo. His content focused on social issues such as wages, prices, and pensions, supplemented with interactive livestreams. His income surged—Hu himself claimed in his programs that, through tips and custom videos, he earned over 600,000 yuan per month.

Hu’s “Apple reversal from an Android life” still rested on a grassroots foundation and grassroots consciousness. His down-to-earth tone, plainspoken style, and satirical humour propelled him to fame, with the public regarding him as a “spokesman for the underclass.”

The livestreamer “Hu Chenfeng” was banned from two major platforms for filming a video of impoverished elderly people shopping.

But controversy emerged in his later livestream debates. When linked online with domestic elites, second- and third-generation wealthy heirs—living in mansions, dripping in gold and luxury, flaunting designer bags and cars, indulging in top-tier consumption, and silently showing off—Hu often displayed great interest and even envy. On the other hand, when interacting with “Android” callers, he sometimes showed impatience or arrogance, occasionally mocking them so harshly that some broke down crying during the live broadcast. These moments and his style of play provided ammunition for “Little Pinks” (pro-CCP nationalists) and other critics to attack him, and also became a flashpoint for heated clashes between opposing camps in his debate streams.

Did Hu truly change for the worse after his successful rise? Even if so, it would not be surprising—he is no saint, and everyone makes mistakes. Hu never tried to wrap himself in a moral halo. While he admired wealth, he never flattered the powerful; while he sought upward mobility, he refused to climb into high society by playing dirty tricks. In his live streams, he openly opposed the “lying flat” mentality among Android people—not out of contempt for the poor, but out of frustration at their lack of ambition. He never echoed official propaganda to attack the underclass. Fans saw him as a “truth-teller” and an “emotional outlet,” though others criticised his content as “low-end anxiety packaging,” shallow attacks on education and family background, and lacking depth. Both, however, fall within the realm of free speech—nothing more, nothing less.

Red Lines Without Protection · Hu’s Social Death · The CCP’s Excuses

On September 20, all of Hu Chenfeng’s programs across every platform were brutally taken down by the CCP authorities. This amounted to an official declaration of Hu’s social death.

The final trigger was a livestream debate with a participant known as “Xiao Zhang,” who clearly came with hostile intent. Hu, a seasoned veteran of the online world and traffic wars, had already suffered harsh lessons: in March 2023, he was censored for posting his “107 Yuan Pension Challenge” video that exposed the struggles of the elderly at the bottom of society; and in July 2025, he was permanently banned from Bilibili and Douyin after a netizen asked him whether Xi Jinping was a dictator. Those bloody experiences taught Hu how to carefully set red lines and avoid sensitive political keywords in his programs. Yet his honest, plainspoken style and straightforward personality left him unguarded against more devious traps.

Xiao Zhang, armed with a meticulously pre-planned logical snare, smooth rhetoric, and fierce attacks, managed to strike at Hu’s weak spot. He attacked Hu’s “Apple vs. Android” thesis, rapidly reframing Hu’s grassroots and people-friendly image as hypocrisy and packaging. He accused Hu’s “love for the people” of being nothing more than a repackaged version of the nationalists’ “love of country.” Hu excelled at logical analysis and institutional critique, but was not versed in the tactics of moral condemnation, as he rarely used moral grandstanding to defeat opponents. A man who had always upheld a moral foundation, Hu ultimately fell to the moral blackmail wielded by another.

After that Waterloo-style debate, Hu was quickly banned. The authorities gave numerous reasons for the ban:

Inciting social division: labelling groups, glorifying “Apples” as elites and “Androids” as the underclass; promoting the “elite city theory,” claiming only six cities with Sam’s Club stores, Apple flagship stores, and international airports are livable.

Disparaging state-owned industries: advocating only Tesla for EVs and only Toyota for gas cars; dismissing domestic technology; predicting that iPhones would monopolise the high-end market.

Challenging public morals: flaunting wealth and disparaging the poor; spreading improper remarks such as “Chinese families’ New Year’s Eve dinners are not as good as McDonald’s” and “the future of Chinese cuisine is pre-made meals.”

Admittedly, Hu Chenfeng’s statements did contain extreme views and biases—such as belittling traditional culture and classical Chinese, or rejecting Chinese medicine. But on the whole, they were simply personal opinions, neither imposed on others nor intended to incite hostility. The CCP’s real reason for silencing him was nothing more than his counter-mainstream values and dissenting speech. In other words, Hu flatly rejected the CCP’s brainwashing rhetoric and propaganda, and successfully pioneered a counter-brainwashing and counter-propaganda model of communication.

Two Zhihu posts sharply analysed the CCP’s motives for banning Hu:

“Hu Sheng’s livestreams fully fit the definition, tone, extreme rhetoric, and propaganda model of ideological colonisation. Coupled with overseas colour revolution groups working in collusion to fuel the flames, he became the focal point of the domestic ‘anti-China for profit’ trend. Privatised healthcare, gender antagonism, privatisation of SOEs, Ukraine, Israel—on all these, he speaks entirely in line with Western subversionist narratives.”

“I once saw a comment that evaluated Hu roughly like this: You can slice society vertically—men hating women, adults hating children, youth hating the elderly, small-city people hating those in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, inland hating coastal—no problem, nothing wrong, that’s even encouraged. But you cannot slice society horizontally. The moment you draw a line dividing Apple people vs. Android people, Apple pensions vs. Android pensions, Apple hospital wards vs. Android wards—that’s a serious violation of livestream regulations. For that, you must be harshly punished.”

The Core Value of the Hu Phenomenon · A Signal of Historical Fracture · Prelude to the CCP’s Final Act

Perhaps Hu Chenfeng will fade from the sight of netizens, but the “Hu Chenfeng phenomenon” and the “Hu whirlwind” have already been etched into the history of the internet as a classic scene, worthy of reflection and discussion.

Why did Hu Chenfeng’s programs resonate so deeply and spark such widespread debate? There are several core value chains that cannot be ignored:

A deep understanding of society’s underclass and livelihood issues: Hu’s videos often focused on the struggles of ordinary people—rising prices, income pressures, and everyday hardships. Much of this came from his grassroots background, which allowed him to truly empathise with people’s pain points and give voice to their concerns.

Solid investigative and research ability: Many of his videos were not just casual talk. He would cite data, use charts, and even personally conduct market research and street interviews. This demonstrated his pragmatic spirit and careful, objective attitude, which greatly enhanced the credibility of his programs.

Critical thinking and independent spirit: Hu’s videos carried strong personal viewpoints. He dared to point out problems and offer his own perspectives, embodying an independent mindset. This is precisely what the CCP deeply fears, as it runs counter to the regime’s rote, indoctrination-style education and propaganda.

Open communication and pushing for a knowledge revolution: Hu’s programs frequently offered basic knowledge-sharing, promoted a “common-sense revolution,” broke through the information gap, and revealed social realities. His international outlook and embrace of universal values such as privatisation and democracy made him a rare clear stream in China’s censored internet, serving as a form of enlightenment education for the “cattle and horses.”

The formula for Hu Chenfeng’s success can be summarised as: grassroots, people-friendly persona + independent thinking + common-sense enlightenment + open debate = the triumph of capitalism and democracy.

Indeed, this is a victory for capitalism. Founders of the Yuanyi and Capital groups, now overseas, commented on Hu’s success, stating that his rise demonstrates the triumph of capitalism: an open internet, free speech, and mobile capital. Even video tips count as capital—someone starting from zero, a complete financial novice, eventually earning hundreds of thousands per month, is a testament to the victory of capitalism.

Although Hu has been banned by the CCP, people’s thirst for truth and reality can never be silenced. The Hu Chenfeng phenomenon has sparked widespread intellectual debate and discussions about truth, proving that the era of Hu Chenfeng is not over—it has only just begun. Before the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the public engaged in extensive debates and reflections on socialist revolution and Soviet history. The historical parallels are striking. The CCP’s censorship is likely to inspire even more citizens to challenge the system mentally. The silencing of speech inevitably triggers the thunder of historical rupture; the prelude to the final chapter of the CCP’s centennial upheaval has already begun.

(First published by People News) △

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!