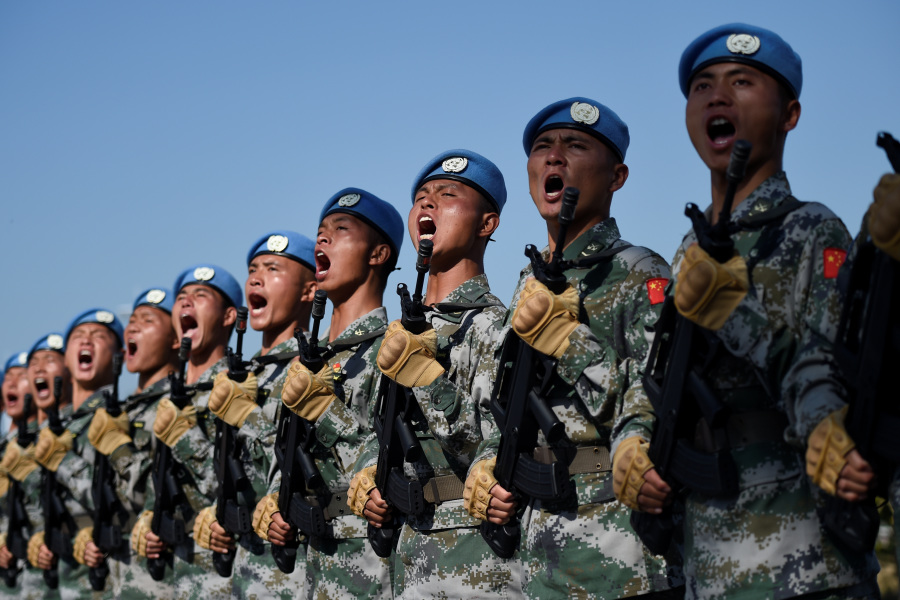

Chinese troops take part in marching drills ahead of an October 1 military parade to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China at a camp on the outskirts of Beijing

[People News] In late January 2026, the Ministry of National Defense announced that Politburo member and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission Zhang Youxia, along with CMC member and Chief of the Joint Staff Department Liu Zhenli, were placed under investigation for “serious violations of discipline and law.”

Shortly afterward, the PLA Daily ran a full-page editorial emphasizing that the two had “seriously trampled on and undermined the system of responsibility of the CMC Chairman” and “seriously endangered the Party’s absolute leadership over the military.” On the surface it was an anti-corruption case, yet the tone repeatedly pointed to military power. The editorial used a striking phrase: Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli “seriously trampled on and undermined the system of responsibility of the CMC Chairman, seriously fostered and impacted the Party’s absolute leadership over the military, and endangered the Party’s ruling foundation through political and corruption problems.”

Throughout the article, the specific details of the usual corruption charges were vaguely described, while phrases such as “political problems,” “CMC Chairman responsibility system,” “absolute leadership,” and “high degree of consistency” were repeated over and over. This indicates that, at least in official discourse, Zhang and Liu’s issue was not merely bribery; the essence was violating political discipline and disturbing the structure of military authority.

Thus, in an instant, the Central Military Commission was left with only two figures: Xi Jinping and Vice Chairman Zhang Shengmin, who oversees discipline inspection—one emperor and one eunuch! For a Chinese Communist Party that claims a glorious revolutionary tradition, such a palace coup is not extraordinary but rather a logical return to the century-old political commandment first articulated at Gutian: the Party commands the gun, not the gun commands the Party. Zhang Youxia’s sudden downfall occurred along the extension of this century-old path.

Overseas media spread claims that Zhang Youxia had leaked nuclear secrets to the United States, a charge widely regarded as absurd at home and abroad. In reality, whether the accusation is true or false is not the key point; what matters is that the charge itself reflects the essence of the matter: Xi Jinping holds the supreme authority to arbitrarily attach even absurd charges to his opponents. Just as Stalin labeled Marshal Tukhachevsky a German spy and had him executed, and Mao Zedong accused Marshal Peng Dehuai of colluding with foreign powers and stripped him of all positions, today Xi Jinping’s personal will has become the will of the state. Zhang’s easy fall demonstrates that the CCP’s internal capacity for self-correction has vanished; contradictions can no longer be resolved within institutional channels, leaving violent suppression or bloody internal conflict as the only possible outcomes.

As CMC Chairman, Xi Jinping reigns supreme; as CMC Vice Chairman, Zhang Youxia stood at the pinnacle beneath him. Such structural tension is difficult to reconcile. Even if Zhang strictly observed his role as a subordinate, suspicion of overstepping was inevitable. Moreover, throughout the history of the international communist movement, no communist political system has ever allowed the gun to command the Party. The CCP has always taken the Soviet Union as its model. Before Mao removed the militarily brilliant Marshal Peng Dehuai at the Lushan Conference, Soviet leader Khrushchev had already easily removed the equally brilliant Marshal Zhukov.

On August 14, 2024, Bi Ruxie said in an interview with Voice of America regarding the Liu Yazhou case: “Those ‘red second generation’ cadres—children of high-ranking officials—all have their views about Xi Jinping. To be frank, people from families at the level of Xi Zhongxun look down on Xi Jinping, whether in terms of his background or his personal qualities. They simply think he drew the number-one political lottery ticket. Given Xi’s personality, he wants to bring down these ‘red second generation’ figures, because only the children of ordinary people are obedient and fearful before him. Xi prefers to maintain the old Beijing compound dynamic, where each privileged child had a group of ‘hutong hangers-on’—ordinary kids—surrounding him, flattering him and giving him a sense of superiority. Today’s Politburo Standing Committee resembles that old courtyard model: Xi as the central privileged child, surrounded by sycophants.”

Now that Xi has removed Zhang Youxia, it appears Bi Ruxie’s prediction has once again, unfortunately, proven accurate.

History’s lessons deserve attention. In 1976, numerous founding marshals and generals were still alive, yet Mao Zedong replaced Marshal Ye Jianying with the mediocre Chen Xilian and forcefully entrusted him with command of the CMC.

Today China’s bureaucratic class is severely ossified. “Red second generation” figures easily occupy key posts, while ordinary citizens’ children find promotion paths blocked, breeding deep resentment toward this modern aristocratic politics. With Xi removing Zhang Youxia, a red-background pedigree may now become a liability, while ordinary-background figures—like Wang Hongwen during the Cultural Revolution—may seize opportunities created by Xi’s purges to rise rapidly. These newly elevated military figures will naturally feel gratitude toward Xi. With shallow roots, they are unlikely to pose a threat, allowing Xi to rest easy.

Zhang Youxia’s résumé reflects a classic professional soldier’s path: enlisted in 1968, long served in frontline ground units, rising from the 14th Army and the 13th Group Army to become commander of the 13th Group Army in 2000; later deputy commander of the Beijing Military Region, commander of the Shenyang Military Region, then head of the General Armaments Department and the CMC Equipment Development Department, eventually entering the CMC and becoming vice chairman and Politburo member—the top military figure at the vice–state level.

His ascent had several features. First, combat experience. Zhang personally fought in the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War and on the Laoshan front in 1984, making him one of the few generals with real combat credentials. He rotated through theater, group army, and military region commands—a commander forged in battle.

Second, deep roots in the equipment system. His father, Zhang Zongxun, once oversaw logistics and equipment systems, leaving a legacy network. After 2012, Zhang Youxia inherited this domain, heading key procurement and research systems—areas rife with corruption risk.

Third, and most crucially, Zhang lacked deep experience in the military political work system. He was not a long-serving political commissar nor deeply embedded in the “political line” of personnel, propaganda, and security. In a normal country, this imbalance would not matter. But in the CCP’s PLA tradition, it is a major vulnerability.

After taking power, Xi convened a 2014 military political work conference in Gutian, repeatedly invoking the “Gutian spirit” and reaffirming absolute Party control and the centrality of political work.

Since then, the line of “Gutian—Party commands the gun—Chairman responsibility system” has dominated military propaganda.

Simultaneously, high-level anti-corruption campaigns swept the military: two defense ministers, numerous Rocket Force officers, and equipment officials fell. Since 2012, over 200,000 officials have reportedly faced discipline.

Military restructuring concentrated power: military regions became theater commands; headquarters were dismantled into CMC departments; the CMC became a smaller body directly answering to the chairman.

From this perspective, Zhang’s fall resembles a correction against the “vice chairman era.” Today only Xi and the discipline vice chairman remain—echoing Mao-era concentration of power.

The 1929 Gutian Conference institutionalized Party control over the army. Mao built a system of party committees and political commissars down to the company level. Even the most powerful commander would be counterbalanced by this web.

After Mao, despite structural changes, “Party commands the gun” remained untouchable. Under Xi, the Chairman responsibility system was elevated as the “lifeline” of absolute Party leadership.

Thus runs the line: Gutian 1929, Lin Biao 1971, and now Zhang Youxia.

Marshal Lin Biao, Mao’s designated successor and vice chairman of the CMC, perished in 1971 in a plane crash officially labeled an attempted coup. Within weeks, thousands of officers were purged. This demonstrated that titles did not determine power—the Party’s political network did.

Today Zhang Youxia, often called Xi’s closest ally, vanished swiftly once investigated. Only brief official statements remain.

Mao set the rules; Xi follows them. Mao’s political legacy of Party control over the gun benefits Xi immensely. Thus Xi’s swift removal of Zhang Youxia is hardly surprising.

(Source: Guang Media www.ipkmedia.com)

△

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!