March 10, 2025, Beijing Great Hall of the People—A security guard stands at the entrance before the closing ceremony of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. (WANG ZHAO/AFP via Getty Images)

[People News] The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), riddled with countless systemic issues and having lost its basic capacity to govern, has suddenly introduced a liquor ban at a time when consumer spending is already in steep decline. Rather than boosting public integrity, the ban has further strangled what little remains of consumer activity.

Small vendors across the internet are voicing their frustration, complaining that the liquor ban has further crushed the already fragile consumer sentiment. Even street food stalls and roadside vendors are now suffering from the ban’s ripple effects. Seeing this backlash, the CCP quickly tried to patch things up, clarifying, “We’re banning illicit drinking, not banning all drinking.”

Since the CCP came to power, it has issued countless directives to curb public spending, including during Hu Jintao’s era, which introduced the now-infamous “four dishes and one soup” policy. Still, extravagant official banquets only grew more rampant over time. For years, local governments flush with funds allowed officials to siphon off public money freely—lavish wining and dining on the public dime became the norm.

This liquor ban, however, is not a genuine effort to clean up the Party's image—its reputation is already in tatters. In reality, the government is simply running out of money. If the lavish banquets continue, all they can do is sit around waiting for collapse. On one side, urban management officers extort money from citizens; on the other, corrupt officials are blowing through state budgets. With the central government realising this imbalance is unsustainable, the liquor ban was hastily imposed.

In a country with no citizen oversight and no free press to expose corruption, all disciplinary rules aimed at officials are empty rhetoric. Xi Jinping has spent over a decade cracking down on corrupt officials, but the problem persists endlessly. Why? Because for every policy from the top, there’s a workaround at the bottom. Public-funded banquets will simply pause until the political wind shifts—and then come back with a vengeance.

Now, with the country plagued by crisis on all fronts, the CCP appears utterly lost, unable to identify root problems or prescribe the right remedies. The most urgent issue isn’t official drinking—it's mass unemployment. Unemployment leaves ordinary people struggling to survive. When the poor have no options, they rebel. Rebellion leads to unrest, and unrest brings down governments.

Yet the CCP, failing to tackle unemployment, chooses instead to push a pointless liquor ban. Not only does this policy lack benefits, but it has further depressed consumer spending. That decline means more small businesses close, causing even more job losses. Even if the ban “succeeds,” fixing unemployment becomes harder—this is political suicide.

What’s more important—reducing unemployment or banning alcohol? This is a question that should’ve been carefully weighed before making any policy decisions. Every policy has indirect consequences, and poorly conceived short-term fixes can cause long-term damage. This is basic decision-making knowledge. The CCP, now in a state of confusion and desperation, imposes this ban merely to appear in control. Yet in trying to demonstrate authority, it has only shown more weakness, especially as it scrambles to clarify or reverse itself.

There are clear and proven ways to reduce unemployment. The simplest is to loosen restrictions on private businesses. But that means treating private firms fairly, stopping their exploitation, and giving them room to grow, just like in the early days of economic reform. Private enterprises contribute 80% of urban jobs and 90% of new employment. If the private sector is allowed to thrive, it will hire more people, increase incomes, and stimulate spending. This is the positive cycle China needs.

Instead, under the “state advances, private sector retreats” policy—and due to local governments being broke—every level of government squeezes private businesses for revenue. Excessive taxes, arbitrary fines, and outright extortion leave many private companies unable to cope. Facing no future, they simply close down or flee, sacrificing employment to prop up the government. In the end, governance weakens anyway.

While local governments are cash-strapped, the central government could save money by cutting bloated bureaucracies. Fire redundant officials and eliminate waste. Many county-level governments have a dozen vice-county chiefs and dozens of departments. Countless public servants draw salaries while doing nothing. Halving this bloat wouldn’t impair operations, but instead of cutting, the CCP continues to raise salaries for civil servants. This is upside-down logic.

To win over mid- and lower-level officials, the regime is willing to alienate private businesses. But as private firms collapse, unemployment soars, and the burden on local governments rises. Ultimately, it is the fragile CCP regime that suffers the most. Back when Li Keqiang was premier, he proposed the “street vendor economy” to boost employment. Xi vetoed it, claiming it would harm the urban image. But what’s more important—city image or jobs? Xi never truly grasped the question.

When people can’t even afford to eat, who cares about how the streets look? A city might look polished on the surface, but if citizens rise up, who cares about the lights?

To seriously fix unemployment, start by firing redundant officials—urban enforcers, grid managers, online propagandists (“50-cent party”), and so on. Use the savings to support local governments and reduce the pressure on private businesses. That’s far better than a liquor ban, which is all bark and no bite, with more harm than help.

Instead of pushing rational, structural policies, Xi introduces a liquor ban. But the money saved is negligible—hardly enough to keep a single local government afloat. The ban might slightly curb official indulgence, but it has dealt a huge blow to grassroots consumption. Lower consumption causes more closures, more unemployment, and greater governance challenges. This vicious cycle is something Xi clearly does not understand.

The real problem may not be that Xi has lost control, but that his cognitive faculties are in decline. His frequent policy failures, and even his awkward reliance on a notebook during his meeting with Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong—struggling to utter even simple pleasantries—suggest deeper issues. A mind operating at that level could easily come up with a half-baked idea like a liquor ban. The nation is falling apart, and he deserves much of the credit.

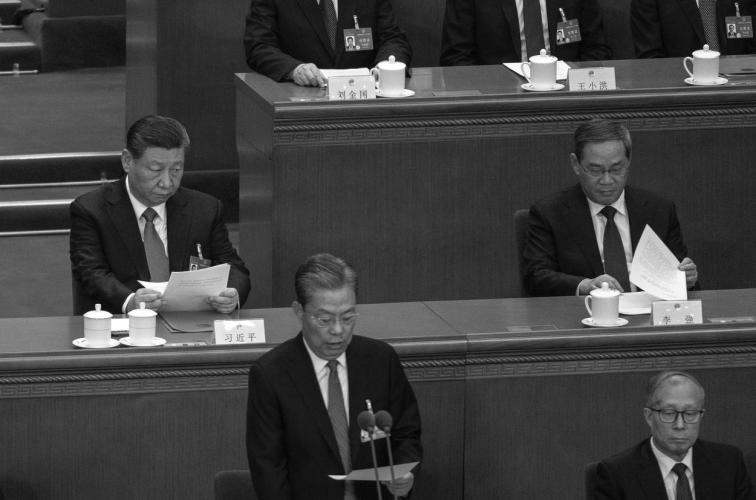

Xi still issues all sorts of directives and meets various leaders, pretending to be visionary. Premier Li Qiang holds endless meetings and inspections, playing the part of a dutiful leader. Everyone appears busy, but no one knows what they’re busy with. Not even they know. The end of a regime arrives when every official watches the ship spring leaks from all sides, doing nothing but waiting for it to finally sink. △

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!