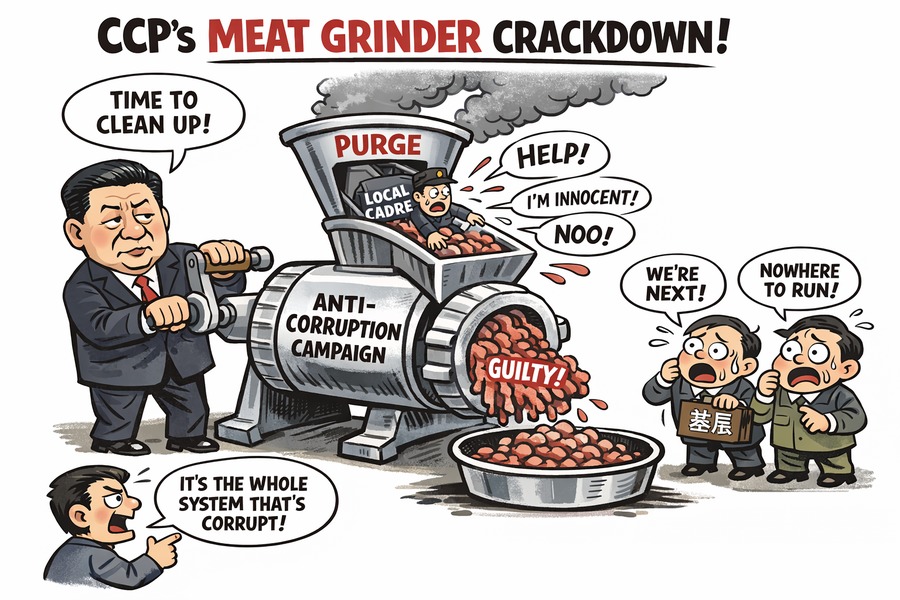

On January 6, 2025, at the plenary session of the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, Xi Jinping stated: "The stockpile of corruption has not yet been eradicated, and new cases continue to emerge..." indirectly admitting the failure of the anti-corruption campaign. (Video screenshot)

[People News] On January 12, Xi Jinping delivered a speech at the Fifth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. He no longer repeated the old refrain that “the anti-corruption struggle has achieved an overwhelming victory and has been comprehensively consolidated,” but instead stated that “anti-corruption is a major struggle that we cannot afford to lose and must never lose.”

Why, after 13 years of Xi’s anti-corruption “tiger-hunting” campaign, is there no talk of how anti-corruption has won, or how to move from victory to even greater victory, but instead talk of anti-corruption as something that “cannot be lost and must never be lost”?

Because harsh reality stands before Xi, and before hundreds of millions of Chinese people — the Chinese Communist Party’s anti-corruption effort has resulted in more and more corruption.

I. The Facts That the CCP Becomes More Corrupt the More It Fights Corruption

In 2025, there were at least three indicators showing that the CCP became more corrupt the more it fought corruption:

First, corruption in the CCP military reached a peak unprecedented in human history.

In 2025, a large number of generals personally promoted by Xi collapsed. Most strikingly, nine full generals, including CCP Politburo member and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission He Weidong — whom Xi personally, exceptionally, and rapidly promoted and reused — were stripped of Party membership, stripped of military rank, and transferred for judicial prosecution all at once.

In 2025, at least 22 full generals who were not officially announced as having fallen but were “disappeared” included: Xu Xueqiang, Minister of the CMC Equipment Development Department; Xu Qiling, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Joint Staff Department; Air Force Commander Chang Dingqiu; Air Force Political Commissar Guo Puxiao; former Air Force Commander Ma Xiaotian; former Army Commander Han Weiguo; Army Commander Li Qiaoming; Army Political Commissar Chen Hui; Navy Commander Hu Zhongming; former Navy Political Commissar Qin Shengxiang; Rocket Force Political Commissar Xu Xisheng; former Rocket Force Political Commissar Xu Zhongbo; Information Support Force Political Commissar Li Wei; Eastern Theater Political Commissar Liu Qingsong; Western Theater Commander Wang Haijiang; Western Theater Political Commissar Li Fengbiao; Southern Theater Commander Wu Yanan; Southern Theater Political Commissar Wang Wenquan; Northern Theater Commander Huang Ming; former Central Theater Commander Wang Qiang; Central Theater Political Commissar Xu Deqing; and National Defense University President Xiao Tianliang.

The officially announced fallen generals and the unannounced “disappeared” generals cover departments of the Central Military Commission, the Navy, Army, Air Force, Rocket Force, the Armed Police Force, the Eastern, Western, Northern, Southern, and Central Theater Commands, and military academies’ political and military leaders.

After 13 years of Xi’s rule, almost all active-duty full generals he promoted have been wiped out. When one full general falls, a group of lieutenant generals and major generals inevitably falls as well. How many lieutenant generals and major generals have fallen so far? The CCP does not dare to disclose this publicly.

The large-scale collapse of so many senior generals is not only a rare spectacle in the 98-year history of the CCP’s military, but also a rare phenomenon in the military histories of countries around the world.

Second, the number of centrally managed officials placed under investigation broke historical records.

Centrally managed officials are those appointed or removed by the CCP Central Committee, including all officials at vice-ministerial level and above, as well as some bureau-level officials.

In 2025, the CCDI website announced that as many as 65 centrally managed officials were placed under investigation, the highest number since the 18th CCP National Congress in 2012. This number does not include senior military generals.

The CCDI once officially announced that from January to September 2025, 90 provincial- and ministerial-level officials were placed under investigation. Adding those non-military centrally managed officials investigated from October to December, the total number of centrally managed officials placed under investigation in 2025 reached 111. This number also broke the historical record since the 18th CCP National Congress.

Moreover, it also broke the historical record for centrally managed officials investigated in any year since the CCP began reform and opening up in 1978 more than 40 years ago.

Third, the number of “100-million-yuan corrupt officials” sentenced to punishment broke historical records.

In 2025, at least 31 corrupt officials involving sums of 100 million yuan or more were sentenced — the highest number since the 18th CCP National Congress. These 31 convicted officials include:

Former Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Deputy Party Secretary Li Pengxin, bribes of 822 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region CPPCC Chairman Qi Tongsheng, bribes of 111 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former CITIC Group Deputy General Manager Xu Zuo, bribes of 147 million yuan, life imprisonment; former Director of the General Administration of Sport Gou Zhongwen, bribes of 236 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Head of the Discipline Inspection and Supervision Group stationed at the CCP Central Organization Department Li Gang, bribes of 102 million yuan, sentenced to 15 years; former New China Life Insurance Chairman Li Quan, embezzlement of 108 million yuan and bribes of 105 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Heilongjiang Provincial People’s Congress Vice Chairman Li Xiangang, bribes of 117 million yuan and embezzlement of 1.68 million yuan, life imprisonment; former Qinghai Provincial Party Standing Committee member and Political-Legal Affairs Secretary Yang Fasen, bribes of 147 million yuan, life imprisonment; former Guizhou CPPCC Vice Chairman Chen Yan, bribes of 357 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Tang Renjian, bribes of 268 million yuan, suspended death sentence.

Former Hainan Provincial People’s Congress Vice Chairman Liu Xingtai, 316 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Vice Chairman Qin Rupai, bribes of 216 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Tibet Autonomous Region Party Secretary Wu Yingjie, bribes of 343 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former vice-ministerial official of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission Luo Yulin, bribes of 220 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Xinjiang CPPCC Vice Chairman Dou Wangui, bribes of 229 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Tibet Autonomous Region Vice Chairman Wang Yong, bribes of 271 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Yunnan Vice Governor Zhang Zulin, bribes of 122 million yuan, life imprisonment; former Hunan CPPCC Vice Chairman Dai Daojin, bribes of 107 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Ministry of Public Security counterterrorism commissioner Liu Yuejin, bribes of 121 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Hunan Provincial People’s Congress Vice Chairman Peng Guofu, bribes of 134 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Shaanxi CPPCC Chairman Han Yong, bribes of 261 million yuan, suspended death sentence.

Former Heilongjiang Vice Governor Wang Yixin, bribes of 129 million yuan, life imprisonment; former Jiangxi Provincial People’s Congress Vice Chairman Yin Meigen, bribes of 207 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Jiangsu Provincial People’s Congress Vice Chairman Liu Handong, bribes of 245 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Hainan Party Secretary Luo Baoming, bribes of 113 million yuan, sentenced to 15 years; former Fujian Provincial People’s Congress Vice Chairman Su Zengtian, bribes of 198 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Qingdao Municipal People’s Congress Vice Chairman Zhang Xijun, bribes of 317 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former China Electronics Technology Group Deputy General Manager He Wenzhong, bribes of 289 million yuan, suspended death sentence; former Shandong Hi-Speed Group General Manager Zhou Yong, bribes of 107 million yuan, life imprisonment; former China Huarong International Holdings General Manager Bai Tianhui, bribes of 1.108 billion yuan, death sentence; former Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Vice President Zhang Hongli, bribes of 177 million yuan, suspended death sentence.

These 100-million-yuan corrupt officials do not include senior military generals. The CCP likely does not dare to disclose the corruption amounts of senior military generals because those sums far exceed those listed above, and it fears that disclosure would provoke rebellion among the military.

Looking across the world, aside from the CCP regime, what other country or region has so many 100-million-yuan corrupt officials sentenced in a single year?

II. Why Does the CCP Become More Corrupt the More It Fights Corruption?

As early as January 2013, when Xi launched the anti-corruption “tiger-hunting” campaign at the Second Plenary Session of the 18th CCDI, he said power must be “locked in the cage of制度.” By February 2025, at the Fifth Plenary Session of the 20th CCDI, Xi was still saying power must be “locked in the cage of制度.”

The key reason the CCP becomes more corrupt the more it fights corruption is that CCP leaders verbally say they want to “lock power in the cage of system,” but in reality they are fundamentally unwilling to do so. How can this be seen? The following three points are sufficient proof:

First, the power of the CCP’s top leader has never been locked in a cage.

After the ten-year Cultural Revolution ended, in light of the catastrophic disasters caused by Mao Zedong’s personal dictatorship, autocracy, totalitarianism, and lawlessness, former CCP Central Organization Department Minister An Ziwen returned to Beijing from exile and asked Bao Tong his first question: “Who supervises Mao Zedong?”

In 2025, 49 years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, for the CCP, who supervises the highest CCP leader? This fundamental institutional question remains unresolved.

The CCP has two institutional documents on anti-corruption: one is the “Responsibility System for Building Party Conduct and Clean Government,” and the other is the “Responsibility System for Promoting Cadres with Illnesses.”

According to these two documents, the highest party, government, and military leader Xi Jinping is the first responsible person for Party conduct and clean government, and also the first responsible person for promoting cadres with “illnesses.”

According to these systems, as the CCP becomes more corrupt the more it fights corruption, Xi must bear the primary responsibility for dereliction of duty in Party conduct and clean government, and must bear the primary responsibility for dereliction of duty in promoting cadres with illnesses.

To this day, has Xi ever made a single self-criticism statement regarding these two “primary responsibilities” he must bear? Searching through all CCP party media reports, not a single sentence can be found.

If Xi himself takes the lead in not complying with these responsibility systems, does the CCP have any practical and feasible制度 to hold Xi accountable for party discipline, administrative discipline, or legal responsibility?

The answer is: no.

The lack of institutional guarantees for supervising the CCP’s top leader is the biggest institutional loophole in the CCP’s anti-corruption effort. If this key issue is not resolved, the CCP’s anti-corruption campaign is like ladling boiling water onto a simmering pot — it will only become more corrupt.

Second, the CCP fundamentally does not want to lock power in a cage.

Looking around the world, countries and regions that have relatively successfully addressed official corruption generally implement systems of asset declaration and public disclosure for officials.

Such systems have three key elements: first, officials proactively declare their assets; second, the public has strong supervisory rights over officials’ declarations, with the ability to review every official’s asset declaration and immediately report falsifications; third, there are powerful supervisory bodies that investigate false declarations or reported fraud in accordance with the law.

Does the CCP know that asset declaration and public disclosure are fundamental solutions to corruption? The answer is: yes. As early as 1988, during the CCP’s “Two Sessions,” NPC deputies proposed legislative initiatives on civil servant asset declaration. In 1994, the Standing Committee of the Eighth National People’s Congress formally included the “Asset Declaration Law” in its legislative plan.

However, to this day, 31 years later, a law on asset declaration and public disclosure for CCP officials has still not been enacted.

Why?

In 13 years, Xi has investigated at least more than 200 generals, yet has not disclosed the specific corruption amount of a single one.

The CCP does not even dare to disclose to the Chinese people the corruption amounts of generals who have already been investigated, let alone require asset declaration and public disclosure for CCP officials who have not been investigated.

A former Singaporean official once said: “If a country does not establish a system of public disclosure of officials’ assets, its anti-corruption efforts can only be flowers in a mirror, the moon in the water.”

The CCP knows full well that asset declaration and public disclosure are fundamental solutions to corruption, yet deliberately refrains from enacting such a system for a long time. What does this show?

It shows that the CCP fundamentally does not want to lock power in a cage. The CCP’s talk of “locking power in a cage” is nothing more than self-deception.

Third, the CCP fears media and public opinion exposure of corruption most of all.

A strong system of media and public opinion supervision is one of the fundamental solutions to corruption. Official corruption fears media exposure, tracking, and in-depth investigation the most. Yet today, the CCP has reached the point of not allowing media and public opinion to supervise corruption at all.

Since the 20th CCP National Congress, from the major Rocket Force corruption case, to the major CMC equipment system case, to the major case involving Miao Hua, Director of the CMC Political Work Department, to the major case involving Politburo member and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission He Weidong, as well as major cases involving the Navy, Army, Air Force, Rocket Force, and Armed Police Force — was there a single case that was publicly exposed by any media outlet before it occurred? No. After the cases occurred, was there a single follow-up report? No. After the cases occurred, was there a single in-depth investigative report? No.

The CCP has continuously covered up, covered up, and covered up again these major cases.

I made a preliminary count: since the 20th CCP National Congress, 35 generals have been officially announced as investigated, including 16 full generals, 15 lieutenant generals, and 4 major generals.

Among them, only the serious disciplinary and legal violations of two full generals were briefly described in reports authorized by the CCP through Xinhua when announcing their expulsion from the Party. These two generals are former Central Military Commission member, State Councilor, and Minister of National Defense Li Shangfu, and former Central Military Commission member, State Councilor, and Minister of National Defense Wei Fenghe.

Regarding Li Shangfu’s serious violations, Xinhua’s report — including punctuation — contained only 102 characters: “Serious violations of political discipline, failure to fulfill political responsibility , resistance to organizational review; serious violations of organizational discipline, illegally seeking personnel benefits for himself and others; using his position to seek benefits for others and accepting huge sums of money; giving money to others to seek improper benefits.”

The message authorized by the CCP Ministry of National Defense announcing that He Weidong and eight other full generals were expelled from the Party was even more concise — including punctuation, only 44 characters: “After investigation, these nine seriously violated Party discipline, are suspected of serious duty-related crimes, with especially huge amounts, extremely serious feature, and extremely bad impact.”

Before Li Shangfu, Wei Fenghe, He Weidong, and the other generals were arrested, all CCP party media supervision of them was effectively zero. After their arrests, aside from the tiny bits of information authorized by the CCP authorities, there was no reporting that constituted lawful media supervision.

The CCP insists that party media must bear the Party’s name, turning them into mouthpieces of those in power, completely losing the function of public opinion supervision.

Conclusion

If the CCP were truly sincere about fighting corruption, it should actively, proactively, and consciously establish and improve institutional systems for the supervision of the CCP’s top leader, asset declaration and public disclosure by officials, and lawful media supervision — and implement these three supervisory systems in practice.

However, to this day, after 76 years of CCP rule, not only has there been no progress in building these three fundamental anti-corruption systems, but instead there has been regression (Mao Zedong at least hypocritically made self-criticisms — has Xi ever made a single self-criticism?), deliberate refusal to legislate, or complete nullification.

How could the CCP’s “anti-corruption” possibly achieve real results? How could it possibly not become more corrupt the more it fights corruption?

— The Dajiyuan

△

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!